Involving citizens and communities in the processes of governance, so that the decisions and actions of those in power are made public, and can be questioned, is key to an efficient Covid-19 response. The role that social accountability can play in the response is an area that we at the Organisation for Social Science Research in Eastern and Southern Africa (OSSREA) are researching for the Covid-19 Responses for Equity (CORE) project on Covid-19 and the Youth Question in Africa: Impact, Response and Protection Measures in the IGAD region.

We are working in collaboration with the Consortium of Christian Relief and Development Associations (CCRDA) of Ethiopia, OSSREA-Kenya Chapter, and the University of Makerere to conduct a rapid baseline study in Ethiopia, Kenya and Uganda. Our aim is to try to understand how the community, especially the youth, is involved in ensuring services are delivered and policies related to the pandemic are designed and implemented in an accountable way. What follows are some reflections on our findings so far.

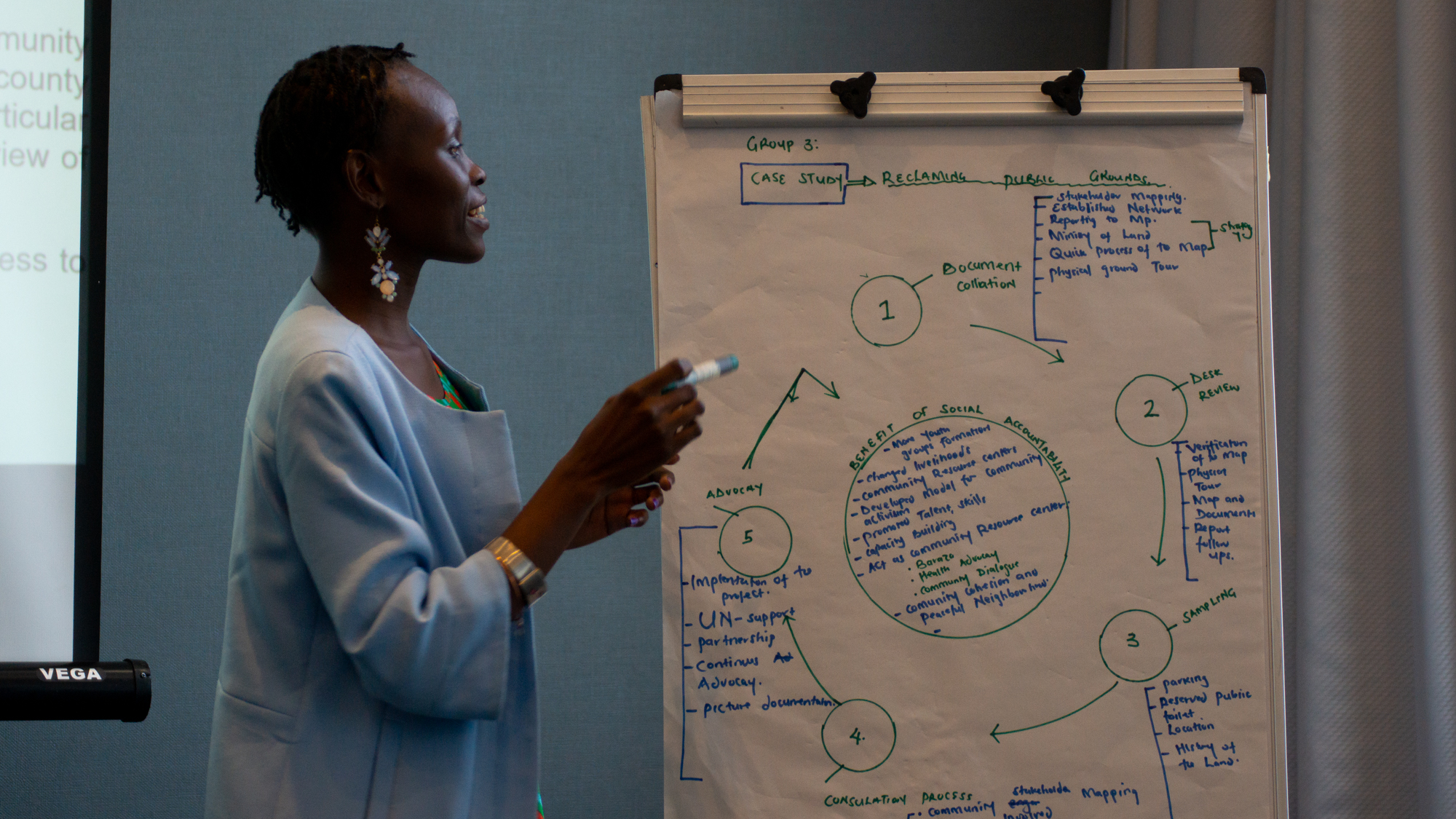

Focus Group Discussion with young people at a youth centre in Likoni, Mombasa Kenya. Credit: OSSREA

Citizen participation

One of the pillars of social accountability is citizen participation, which is the right of citizens to actively play a part and offer feedback in local governments’ decision-making processes. Citizen engagement in budget formulation, strategic planning, complaints systems, as well as the use of disagreement resolution mechanisms are forms of meaningful participation. The government – at various levels – is expected to provide support for enabling an appropriate environment for negotiation.

The rapid baseline study in all three countries revealed that limited youth participation existed when it comes to providing feedback to local and national government decision-making processes. The Covid-19 response was designed and implemented, almost exclusively, by central governments, and focused predominantly on giving people information about the pandemic and increasing the availability of protective materials. In addition, lockdown, and its stern enforcement by the security forces, kept youth out of the response.

Notably, in all three countries, awareness about policies on youth participation in the Covid-19 response was low. In Nairobi, 63% responded that young people were not able to participate due to their lack of knowledge on their rights, responsibilities, and entitlements. In Uganda, 60% of them were not mobilised by state or non-state actors to participate in the response. In Ethiopia, 83% of participants reported that they were not aware of any policy on youth participation in the Covid-19 response.

Transparency

Transparency – another pillar of social accountability – is about supporting processes that enable access to information for citizens in the public domain. This may include systematic reporting on local government operations, budgets and expenditures, public programmes, and new policies and priorities. It also refers to increasing citizen awareness and understanding of laws, rights, budgets, and policies through public campaigns, and enabling collective action by civil society organisations (CSOs), the media and stakeholder coalitions.

Our study revealed that while information on the pandemic, and measures to follow, was shared with the public, little was communicated to the community and youth around government operations, budgets and expenditures. The youth interviewed reported very limited knowledge of new government policies and priorities in response to the Covid-19 pandemic, with 74% of respondents in Nairobi and 90% in Kampala not involved or aware of the Covid-19 response budget allocations. In Addis Ababa, 74% of the participants indicated that the Covid-19 response budget was not made public.

To address this, some youth-based CSOs at national and local levels, in all three countries, have engaged with the media or aired their concerns on social media.

Monitoring

We also looked into monitoring, i.e., the systematic collection and analysis of information to enable stakeholders, as third-party monitors, to determine whether local governments are implementing their responsibilities according to the law. This includes national government and citizen monitoring of local governments’ budgets, effectiveness, and service delivery through mechanisms such as participatory monitoring (social audit), budget tracking, media investigations, independent budget and policy analysis, formal oversight mechanisms (parliamentary committees), and multi-stakeholder commissions.

Our findings revealed that very minimum involvement of the youth and youth-based organisations exists in assessing and monitoring services. Some youth-based organisations informed us that continuing face-to-face monitoring in some of their programmes was not possible due to the pandemic. Furthermore, according to respondents in all three countries, despite being aware of their local government failing to uphold their legal responsibilities, they don’t have the means or mechanisms to demand information from the people implementing activities in the Covid-19 response, and formally monitor and report cases. In Uganda, 68% of the youth reported being aware of embezzlement of Covid-19 resources and yet, they were not aware of any mechanism to address this challenge. Corruption was an issue reported in all three countries, with 82% of the respondents witnessing it in their community in Kenya, and 61% in Ethiopia.

Feedback

The study also explored the capacity and willingness of local government to identify and respond to citizen needs and preferences, as well as local government request for citizen feedback. This includes feedback on citizen complaints, response to needs assessments, performance awards, service delivery innovations, and forums to introduce specific government policies.

Our research found that reaching officials to get problems solved was difficult because of the pandemic and lockdown policies. To overcome these hurdles, some youth-based organisations informed us that they were able to contact duty bearers remotely via WhatsApp messages and phone calls. The findings show that little was done in engaging citizens to hold service providers accountable.

Much remains to be done by state and non-state actors to enhance youth engagement in social accountability. This is necessary in order to promote recovery from the Covid-19 pandemic in a better way and adhere to the ‘build back better’ strategy adopted by UN member states.